Contemporary Positionalities of Women in the Arts: Anita Magsaysay-Ho, Nena Saguil, and Pacita Abad

At this point, there is no contention on the importance and role of women artists.

There are arguments that push for dropping the label "woman/women" altogether and simply calling them artists. Of course, that has always been the aim—but looking into the context of art history, women’s positionality in the arts has always been complicated. Through the years, it was akin to playing catch-up in terms of privileges, access, and recognition. And the conversation on the lack of a National Artist for Visual Arts who is a woman is back. Do we simply not have a woman qualified as a National Artist for Visual Arts?

In 1971, Linda Nochlin posed the question of context in "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" It is not a matter of a lack of, but rather the context and the position we have placed women artists in. More than 50 years later, with so many changes—have we answered the difficulties Nochlin presented? Or, much like in the 1970s, is it still complicated?

Materials in Practice

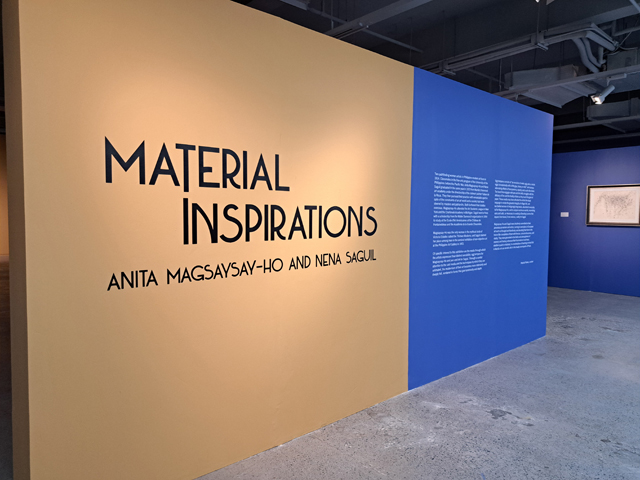

Patrick Flores’ curation of Material Inspirations: Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil veered away from positionalities often anchored to exhibitions of women artists. Rather, he focused on the materials and methods Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil developed at particular junctures of their respective careers—egg tempera for Magsaysay-Ho and pen on paper for Saguil.

Material Inspirations: Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil runs until December 8 at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

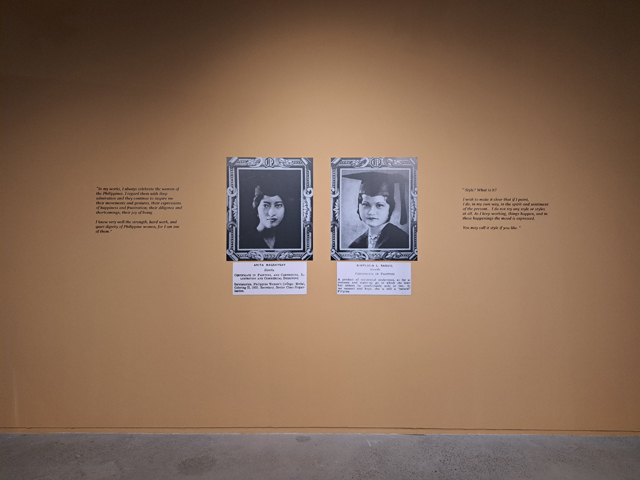

Both women, born in 1914, studied painting at the University of the Philippines under the directorship of Fabian de la Rosa. Flores’ choice of featuring pages from The Philippinensian presented a cover page of the Fine Arts department with a male painter painting a female nude. Included as well is a quote from Genesis 1:27, "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." Though not a direct framework for Material Inspirations—gendered discourse is inescapable, especially when looking into women artists from the 20th century.

Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil

Egg Tempera as Medium

Magsaysay-Ho’s section presented her egg tempera paintings, as well as her studies and photographs. One key element under the glass case is her recipe and method for the egg tempera. The method can be traced back to antiquity and is tedious to use as it dries quickly, and its luminosity necessitates layered application. The result, of course, gives a certain glow and depth to the paintings. Discoloration is also minimal, sustaining the colors and brushstrokes the artist intended in the work. Magsaysay-Ho’s fascination with the development of the medium made her works distinctive from her contemporaries. As fragile as comparisons often are—she is the only woman named by Victorio Edades in the Thirteen Moderns.

Transitions from Academic to Modern

The difference in Magsaysay-Ho’s style and technique in developing egg tempera is seen in the two Gleaners paintings: "Nag-iipon ng Dayami/The Gleaners" (1947) and "Women Gleaners" (1956).

'Nag-iipon ng Dayami/The Gleaners' (1947) by Anita Magsaysay-Ho

'Women Gleaners' (1956)

The pastoral scene, combined with the traditional depth of field as well as softer lines, shows the influence of academic background and training despite the early display of experimental compositions. In less than a decade, the remnants of academic style fade away as she constructs her images to fill the canvas. The colors have more depth, and though the subject matter remains the same, the modernist approach is palpable in the 1956 work. She has also opted out of including a male figure and began focusing on female figures—which would feature more heavily as her career develops.

Flores’ curatorial approach layers different moments of the artist’s work—presenting the painting, a study, and an undated documentary photograph featuring the work in the artists’ studio: "Pagbabayo/ Pounding Rice" (1950), "Pagbabayo/ Pounding Rice" (1947), and a photograph of Anita Magsaysay-Ho taken from her retrospective. At this point, Magsaysay-Ho trained at the Cranbrook Academy in Michigan and the Art Students League in New York City. She married, had children, and eventually traveled extensively with her family while continuing her practice of painting Filipino women in rural scenes. Magsaysay-Ho left an indelible mark in Filipino art history despite the dominant male and academic establishment.

'Pagbabayo/ Pounding Rice' (1950), 'Pagbabayo/ Pounding Rice' (1947), and an undated photograph of Anita Magsaysay-Ho from her retrospective

Exploring Interconnections

Flores found many ties intertwining Magsaysay-Ho and Saguil—their birth year, their study at the University of the Philippines, and even their respective retrospectives at The Metropolitan Museum of Manila. In 2006, both were awarded the Presidential Medal of Merit.

For Saguil’s part in the exhibition, much of the pen-and-ink works were created during her stay in Europe. She eventually established herself in Europe by studying at the Ecoles d’Art Américaines de Fontainebleau, the Institute of Spanish Culture, and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. She had a fulfilling and successful career in Europe, particularly in Paris, starting with her first exhibition at the Galerie Raymond Creuze.

Abstract as Form

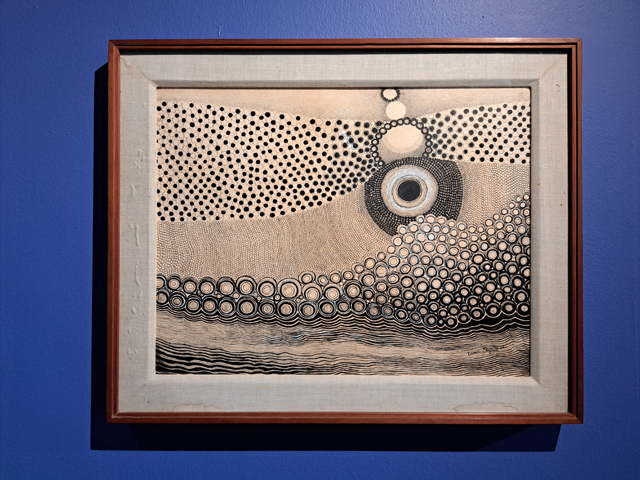

Saguil completely broke away from the academic style and training she received in the Philippines—working mostly on abstraction. For Material Inspirations, Flores focused on the mesmerizing pen-and-inks. Though there may have been theories and searches for references in Saguil’s abstractions, it is best engaged with as an abstract work—exploring each line and stroke, finding the scratches and imperfections. The focus on the details and movements is a journey in and of itself. Looking at the work as a whole and then exploring the characteristics of each work is meditative and, at the same time, cerebral. Saguil’s untitled 1964 work, larger than most of her works on paper, invites a closer inspection, with a bench positioned exactly for the purpose.

Untitled (1964) by Nena Saguil

As arresting as her large-scale works, especially as they are rarely seen in the country. The smaller-scale ones are just as fascinating. Her untitled works from 1962 and 1963 combine pen and ink with watercolor, and the looseness and often uncontrollable watercolor medium intertwine with the solid lines of ink. One particularly interesting piece is an untitled work from 1972, where correction fluid is found among her circles and lines. Are these on purpose? Were mistakes corrected? Or is there a purposeful avoidance of perfection in embracing the layers of her works?

Untitled (1962), Untitled (1963)

Untitled (1972)

Saguil’s embrace of abstraction and modernity makes her an emblematic figure in Philippine art history. Though she started her art education and practice in the Philippines under notable academic style painters, she managed to create her own style and practice, though much of it in Paris. Per Flores, Saguil did very well in the art markets of Paris, and her works were much appreciated. Her works do not hold a trace of tradition and the burden of academic style—rather, Saguil was emboldened to create and explore a unique practice not tied down to peers dominating the local scene at the time.

Identity as a Filipino Painter

A few weeks after opening Material Inspirations, the Metropolitan Museum of Manila launched Pacita Abad: Philippine Painter, bringing in another curator from the National Gallery Singapore, Clarissa Chikiamco. This is also Chikiamko’s homecoming exhibition, as she hasn’t done a curatorial project in the country in years—focusing her practice in Singapore. The narrative resonates well with the globality of the narrative, tying the three artists together: Magsaysay-Ho, Saguil, and Abad. Both Flores and Chikiamco, though Filipino origins, are now part of the curatorial team of the National Gallery Singapore, and much like the artists they curated, their current practice is anchored on globality and diaspora.

Pacita Abad: Philippine Painter runs until March 30, 2025, at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

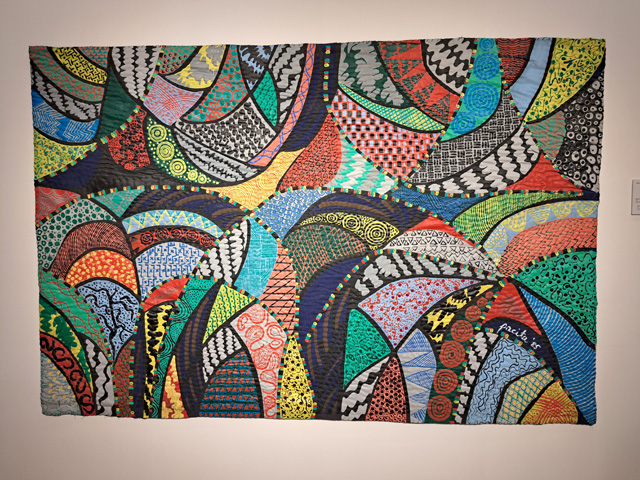

Chikiamco’s curatorial approach anchors on establishing Pacita Abad as a Filipino painter—making identity a key point in the exhibition. She used works created during Paz’s stay in the Philippines between 1976 and 1986 and are currently part of collections within the country. The texts were also translated into Filipino, conscious of the identity formation the exhibition was establishing. Vivid Colors: Katingkaran presented Abad’s early works, which were on the rougher side and leaning towards modern influences such as the Fauves and German expressionists. Chikiamco pointed toward the oil on canvas "Butterfly" (1976), demonstrating how different her work of the same title would be: the mixed media on oil and fabric "Butterfly" (1985), where her well-known trapunto technique will come into play. Sewing together fabric and then painting on them traverses the limitations placed on craft and art, later becoming a signature for Abad.

Vivid Colors: Katingkaran

'Butterfly' (1976) by Pacita Abad

'Butterfly' (1985)

Travel and Diaspora

Much like Magsaysay-Ho, Abad also traveled a lot with her husband. Their global encounters featured in A Philippine Painter Looks at the World: Isang Pilipinong Pintor Tumatanaw sa Mundo. Travel influenced her work, from lighthearted paintings "Children of Paradise" (1977) featuring the Paris Opera House and "Surma Bridge in Bangladesh" (1978), purposely presenting the beauty of Shylet.

'Children of Paradise' (1977)

'Surma Bridge in Bangladesh' (1978)

More notable are her paintings, which served as a sociopolitical commentary on the refugee situation in Thailand as Cambodians fled the Khmer Rouge. Her Portraits of Cambodia series, including "Daily Rations" (1980) and "Woman of the World" (1980), looked into the harsh conditions the refugees had to survive in the crisis. Her political background definitely plays a part in her rougher, more honest works.

'Daily Rations' (1980) and 'Woman of the World' (1980)

Experimental Forms and Political Climate

Undeniably, Abad’s strongest works are her large-scale trapuntos. Painting on sewn and quilted fabric gives a dynamic feel to her artworks. Categorized as painting, she was known to work and rework until she was happy with the piece. Featured in the section To See the Country Through the Eyes of a Painter: Makita ang aking Bayan sa mga Mata ng Isang Pintor, her large-scale "Pacita Sailing" (1983/1987) demands attention. Considered a self-portrait, her excitement for her first trip to Indonesia resonates in the vibrant colors and bold lines of the painting. Displaying the work in the middle of the section highlights its quality, giving a glimpse of the details available at the back of the work.

'Pacita Sailing' (1983/1987)

Abad left the country in 1986 as the political turmoil hit a boiling point. Before then, she would paint "Mendiola" (1984), a painting of a soldier in front of a barbed wire fence with a white building in the distance. Mendiola is a street near Malacañang Palace, the seat of the President of the Philippines, where protests often happen. The painting came out a year after the assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino Jr, then a leading personality in the opposition. The political climate in the Philippines is at a breaking point, and Abad’s sensitivity to the current conditions is notable.

'Mendiola' (1984)

Batanes, her life in the Philippines, and her love of water would endure in many of Abad’s works. The M exhibition ended at a high point—calling back to her 1986 solo exhibition at the Ayala Museum, Assaulting the Deep Sea. The exhibition, shown in a video clip, was immersive, with the only installation Abad worked on and presented in her career. It concludes the strong point and, at moments, a touch heavy-handed, that she is a Filipino painter tied to her roots as Ivatan, and bringing her identity as a Filipino along with her through her artistic journey.

'Sumilon Island' (1986)

Exhibiting and Framing Women Artists

The two exhibitions featuring three important women artists is a monumental time for The M. The ideas of identity, the role of women in the arts, the numerous artistic challenges, and the expertise and breakthrough brought about by Magsaysay-Ho, Saguil, and Abad should be exhibited, talked about, written about, and explored more—given the current landscape of Philippine art. There are important touchpoints here—the undeniable privileges the artists enjoyed, the access to training and travel, and the available support they received as they grew in their respective careers. They paved the path for women artists and Filipino artists, something much more difficult at their time, and it was a great thing they had support. The question of National Artist for Visual Arts remains and perhaps the first woman recognized will be one of them (excepting the issue of Magsaysay-Ho’s citizenship).

Going Beyond Institutional Recognition

Outside of the coveted national recognition, it is perhaps more important that they become more of a household name in the arts in a way that everyone knows Fernando Amorsolo. Exhibitions, presentations, research, publications, social media content, and much more would communicate to the public who these women are, their work and style, their life, and the mark they made in Philippine art. It is a consistent journey undertaken.

Beyond identifying who the great women artists were and are—the details about their work, the sociopolitical context of their work, the importance of privileges and access, and the nuances in their positionalities as individual artists and their place in the artwork are conversations that should be more commonplace when we talk about artists, women artists, artists in the diaspora, global artists, global south artists, and many other complicated labels that are entangled in the practice.

Material Inspirations: Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil runs until December 8 at the 3/F South Gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. Pacita Abad: Philippine Painter runs until March 30, 2025, at the 3/F North Gallery, also of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

The Metropolitan Museum of Manila is at MK Tan Centre, 30th Street, Bonifacio Global City. It is open from Tuesday to Friday, from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; and from Saturday to Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.